בקיץ 1959 פירסם המשורר והמבקר הצרפתי Charles Baudlaire מניפסט חריף נגד ה"אספסוף הבורגני" ש"סוגד לאל השמש ול-Daguerre משיחו". בודלייר התרעם על עליית קרנו של הצילום כאמנות החדשה. לדידו הצילום הוא טכניקה חלולה, חסרת רגשות ותיאורית בלבד. חסר בו הביטוי הנפשי שמאפיין אמנות. כל ערכו הוא ברפרודוקציה שטוחה של הטבע ורפרודוקציה, מהימנה ככל שתהיה, איננה אמנות. המניפסט של בודלייר מלא בארס אריסטוקרטי. הוא משתמש בלשון חריפה כל כך עד שמפליא שהמסמך חמק מעיניהם הבוחנות של הצנזורים של נפוליאון ה-III (שנתיים קודם לכן הוחרמו שישה משיריו בטענה שהם חותרים תחת המוסר הציבורי). הנה חלק ממנו, בעריכתו ובתרגומו לאנגלית של Jonathan Mayne:

[…] During this lamentable period, a new industry arose which contributed not a little to confirm stupidity in its faith and to ruin whatever might remain of the divine in the French mind. The idolatrous mob demanded an ideal worthy of itself and appropriate to its nature – that is perfectly understood. In matters of painting and sculpture, the present-day Credo of the sophisticated, above all in France (and I do not think that anyone at all would dare to state the contrary), is this: “I believe in Nature, and I believe only in Nature (there are good reasons for that). I believe that Art is, and cannot be other than, the exact reproduction of Nature (a timid and dissident sect would wish to exclude the more repellent objects of nature, such as skeletons or chamber-pots). Thus an industry that could give us a result identical to Nature would be the absolute of Art.” A revengeful God has given ear to the prayers of this multitude. Daguerre was his Messiah. And now the faithful says to himself: “Since photography gives us every guarantee of exactitude that we could desire (they really believe that, the mad fools!), then photography and Art are the same thing:’ From that moment our squalid society rushed, Narcissus to a man, to gaze at its trivial image on a scrap of metal. A madness, an extraordinary fanaticism took possession of all these new sun-worshippers. Strange abominations took form. By bringing together a group of male and female clowns, got up like butchers and laundry-maids in a carnival, and by begging these heroes to be so kind as to hold their chance grimaces for the time necessary for the performance, the operator flattered himself that he was reproducing tragic or elegant scenes from ancient history. Some democratic writer ought to have seen here a cheap method of disseminating a loathing for history and for painting among the people, thus committing a double sacrilege and insulting at one and the same time the divine art of painting and the noble art of the actor. A little later a thousand hungry eyes were bending over the peepholes of the stereoscope, as though they were the attic-windows of the infinite. The love of pornography, which is no less deep-rooted in the natural heart of man than the love of himself, was not to let slip so fine an opportunity of self-satisfaction. And do not imagine that it was only children on their way back from school who took pleasure in these follies; the world was infatuated with them. I was once present when some friends were discretely concealing some such pictures from a beautiful woman, a woman of high society, not of mine—they were taking upon themselves some feeling of delicacy in her presence; but “No,” she replied. “Give them to me! Nothing is too strong for me.” I swear that I heard that; but who will believe me? “You can see that they are great ladies,” said Alexandre Dumas. “There are some still greater!“ said Cazotte. As the photographic industry was the refuge of every would-be painter, every painter too ill-endowed or too lazy to complete his studies, this universal infatuation bore not only the mark of a blindness, an imbecility, but had also the air of a vengeance. I do not believe, or at least I do not wish to believe, in the absolute success of such a brutish conspiracy, in which, as in all others, one finds both fools and knaves; but I am convinced that the ill-applied developments of photography, like all other purely material developments of progress, have contributed much to the impoverishment of the French artistic genius, which is already so scarce. In vain may our modern Fatuity roar, belch forth all the rumbling wind of its rotund stomach, spew out all the undigested sophisms with which recent philosophy has stuffed it from top to bottom; it is nonetheless obvious that this industry, by invading the territories of art, has become art’s most mortal enemy, and that the confusion of their several functions prevents any of them from being properly fulfilled. Poetry and progress are like two ambitious men who hate one another with an instinctive hatred, and when they meet upon the same road, one of them has to give place. If photography is allowed to supplement art in some of its functions, it will soon have supplanted or corrupted it altogether, thanks to the stupidity of the multitude which is its natural ally. It is time, then, for it to return to its true duty, which is to be the servant of the sciences and arts— but the very humble servant, like printing or shorthand, which have neither created nor supplemented literature. Let it hasten to enrich the tourist’s album and restore to his eye the precision which his memory may lack; let it adorn the naturalist’s library, and enlarge microscopic animals; let it even provide information to corroborate the astronomer’s hypotheses; in short, let it be the secretary and clerk of whoever needs an absolute factual exactitude in his profession—up to that point nothing could be better. Let it rescue from oblivion those tumbling ruins, those books, prints and manuscripts which time is devouring, precious things whose form is dissolving and which demand a place in the archives of our memory—— it will be thanked and applauded. But if it be allowed to encroach upon the domain of the impalpable and the imaginary, upon anything whose value depends solely upon the addition of something of a man’s soul, then it will be so much the worse for us!

I know very well that some people will retort, “The disease which you have just been diagnosing is a disease of imbeciles. What man worthy of the name of artist, and what true connoisseur, has ever confused art with industry?” I know it; and yet I will ask them in my turn if they believe in the contagion of good and evil, in the action of the mass on individuals, and in the involuntary, forced obedience of the individual to the mass. It is an incontestable, an irresistible law that the artist should act upon the public, and that the public should react upon the artist; and besides, those terrible witnesses, the facts, are easy to study; the disaster is verifiable. Each day art further diminishes its self-respect by bowing down before external reality; each day the painter becomes more and more given to painting not what he dreams but what he sees. Nevertheless it is a happiness to dream, and it used to be a glory to express what one dreamt. But I ask you! does the painter still know this happiness?

Could you find an honest observer to declare that the invasion of photography and the great industrial madness of our times have no part at all in this deplorable result? Are we to suppose that a people whose eyes are growing used to considering the results of a material science as though they were the products of the beautiful, will not in the course of time have singularly diminished its faculties of judging and of feeling what are among the most ethereal and immaterial aspects of creation?

Charles Baudlaire, Salon of 1959, Révue Française, Paris, June 10-July 20, 1859 from: Charles Baudelaire, The Mirror of Art. Jonathan Mayne editor and translator. London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1955

|

| Félix Nadar, Charles Baudlaire, 1855 |

דבריו של בודלייר מבטאים דילמה אמיתית שניצבה בפני צלמים מאז אמצע המאה ה-19: הדמיון של התצלום למציאות גרם לחוסר נוחות אצל חלקם. כבר בחודשים הראשונים שלאחר פרסום שיטת קיבוע התמונה בקאמרה אובסקורה בראשית שנת 1939 עמדו בפני הצלמים שתי אלטרנטיבות טכנולוגיות: ה-daguerrotype הצרפתי השתמש בלוח מתכת וקיבע בו תמונה פוזיטיבית, בעוד ה-calotype הבריטי השתמש בנייר מרוגש לאור וקיבע בו תמונה נגטיבית. הטכנולוגיה הצרפתית הציעה מידת פירוט וחדות עדיפות ואיפשרה משך חשיפה קצר בהרבה, ולכן הועדפה ע"י רוב הצלמים עד שפיתוחים טכנולוגיים בשנות ה-60 של המאה ה-19 שיפרו איכות התמונה שהתקבלה מנגטיבים של נייר. אבל דווקא בצרפת, מולדתו של ה-daguerrotype, תקע ה-calotype יתד איתן: ב-1851 הוקם ה-Missions Héliographiques, חברה ממשלתית שתפקידה היה תיעוד של אתרים היסטוריים ברחבי צרפת באמצעות צילום. Prosper Mérimée, מייסד החברה ומנהלה, תיעב את הדיוק הרב ואת המראה המתכתי של ה-daguerrotype וחש שהנייר הוא מדיום מתאים יותר לתיעוד היסטורי.

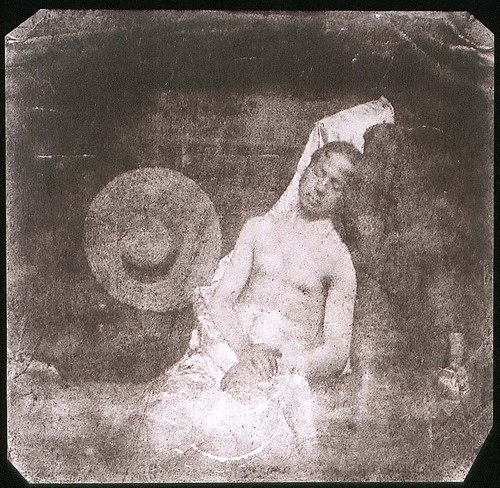

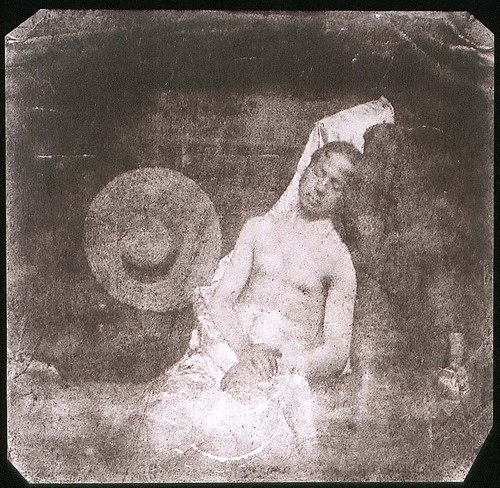

הדוגמאות לצילום פיקטוריאליסטי ("צילום דמוי ציור") באמצע המאה ה-19 מעטות אבל חשובות מבחינה היסטורית. הביקורת של בודלייר חושפת התלהבות עצומה מהצילום, שהציתה את דמיונו של המעמד הבינוני במערב אירופה ובארצות הברית. חתירה נגד הזרם הזה הבטיחה כישלון מסחרי. ובכל זאת, מספר צלמים ראו בצילום מדיום מתאים לביטוי אמנותי ויצרו תמונות שונות למדי מהפורטרטים, ה-cartes de visite (פורטרטים זעירים), תצלומי האתרים ההיסטוריים וה-tableaux vivants (סצנות תיאטרליות קפואות) ששלטו בצילום המסחרי (אה, כן. שכחתי את הפורנוגרפיה). הראשון שבהם היה ככל הנראה הצלם הצרפתי Hippolyte Bayard (י1807-1887) שפירסם עוד בשנת 1840 את התצלום "פורטרט עצמי כאיש טבוע". במהלך שנות ה-40 התפרסם Bayard בנופים ה"מרחפים" שלו. הוא הרבה להשתמש בתנועה קלה של המצלמה תוך כדי החשיפה על מנת לקבל תמונה כפולה או משולשת.

|

| Hippolyte Bayard, Self portrait as a drowned man, 1840 |

הצלם הנודע Nadar (י1820-1910), אמן פריסאי רב כשרונות שהחל את הקריירה שלו כקריקטוריסט, פתח סטודיו אופנתי לצילום בראשית שנות ה-50. נושאיו העיקריים היו דמויות הבוהמה הפריסאית של תקופתו. למרות שהוא צילם פורטרטים, עינו החדה הצליחה לחדור מבעד לחזות הקפואה של המצולמים ולגלות טפח מאופיים ומהשקפת עולמם. למשל, הפורטרט של הסופר והמחזאי Théophile Gautier מרמז על הבוז שחשו הן המצולם והן הצלם כלפי ערכי הבורגנות.

|

| Félix Nadar, Théophile Gautier, 1856 |

Julia Margaret Cameron (י1815-1879), בת אצולה בריטית, קיבלה מצלמה במתנה כשהיתה בת 48 ומאז צילמה אישי תרבות ומדע בני תקופתה כמו גם tableaux vivants. רבים מהתצלומים שיצרה הצטיינו במיקוד לא מושלם, שנתן להם איכות אקספרסיוניסטית "חלומית". הגיל המתקדם, ההיכרות המועטה של צלמים אחרים וההשכלה האמנותית הבסיסית העניקו לקאמרון תעוזה יצירתית ויכולת עמידה מרשימה בפני הביקורת מצד עמיתיה. אני אוהב מאד את מה שיצרה.

|

| Julia Margaret Cameron, Beatrice, 1870 |

.